What is Twang?

ABSTRACT

Adding 'twang' to the voice is a natural way to help your voice project. It involves a narrowing of the space above the larynx to intensify certain resonant frequencies. It's a very safe way to make your voice stronger, without adding any more vocal effort. It is NOT inherently nasal and is produced in the throat NOT the nose.

What is Twang? by Andy Follin

Twang or twang?

Before I delve too far into this, it's useful to define some terms. Singers often talk about 'adding twang' to the voice, and also 'singing in Twang'. These are not quite the same thing. Twang (with a capital "T") is one of the Six Voice Qualities defined by the Estill model. twang (with a lower case "t") is another term for an intentional narrowing of the vocal tract, in the space above the larynx (epilarynx). In the Estill model, this is referred to as the Ary Epiglottic Sphincter (AES for short), so adding twang means narrowing the AES.

For the purposes of this article, I'll refer to the Voice Quality as Twang when necessary, but the bulk of the article will be discussing twang i.e. the narrowing of the epilarynx. In simple terms, Twang is a recipe and twang is an ingredient, and twang (the ingredient) can be used in a number of different recipes / Voice Qualities, not just Twang - for example, in Belt, Mix and also Opera quality.

The effects of twang

A narrowed epilarynx:

- Boosts specific resonances

- Adds energy to your sound

- Cuts through background noise

- Makes the voice easier to be heard

- Makes vocalising more efficient

- Evokes a Primal response

These effects are not limited to singing. Twang is often present in certain spoken accents - Australians, Americans and inhabitants of certain UK cities (e.g. Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham, Glasgow) all have an inherent amount of twang in their speaking voices. Twang is also a component of different languages like Italian and Chinese.

The theory is that adding twang to your speaking voice helps your voice carry through the background sounds of a busy city, so is a learned behaviour, formed from an early age.

Twang by other names

Singers and teachers use a number of different terms when referring to this energy boost, for example:

- Ring

- Squillo

- Projection

- Edge

- Blade

- Singers Formant Cluster

These terms tend to be genre-specific (e.g. CCM singers may refer more to "Edge", Classical singers more to "Squillo") but they're essentially describing a similar thing i.e. a boost in specific resonances.

Later in this article, I'll discuss the subtle differences between a CCM twang and a Classical twang, but for now, we'll just look at the basic concepts.

Is twang nasal?

twang is NOT formed in the nasal cavities

A common misconception is that twang is a nasal sound.

Nasality occurs when the soft palate lowers and allows some or all of the sound into the nasal cavities. ANY voice quality can be nasalised. If this is done intentionally by the singer (to portray a 'character' voice, for example) then it is a deliberate artistic choice and perfectly valid.

Due to the complex muscular connections of the larynx, the soft palate can sometimes be lowered by accident, resulting in an unpleasant 'whiney' sound - think Kenneth Williams in the Carry On films.

The Soft Palate

When you sing, the sound produced by the vibration of the vocal folds is amplified and resonated in the vocal tract (throat and mouth). The Soft Palate (velum) is a structure in the vocal tract which opens and closes the doorway to the nasal cavities.

The Soft Palate is deliberately lowered when we form nasal consonants ("mm","nn","ng").

Sometimes, the Soft Palate unintentionally lowers, resulting in a nasalised tone of voice.

Lowering the soft palate results in a dampening of high frequency energy - in other words, the voice gets duller. Speakers who have a consistently dull voice may well have discovered (by accident or design) that adding twang to the sound helps them to be heard. This may be the reason why there's a general perception that 'twangy' voices are nasal.

Twang explained

To understand twang fully, we need to understand it in terms of two related but separate elements - the acoustics (what the audience hears) and the anatomy (how the singer produces it).

The acoustics of twang

Narrowing the epilarynx has three major effects on the voice:

- It adds energy in the acoustic spectrum

- above speaking range (2kHz upwards)

- in the range we hear best (biologically 'tuned')

- creating a sympathetic vibration in the ear canal of listeners (and singer!)

- Evokes a Primal response in the listener

- Attention grabbing / annoying (depending on context!)

- Makes vocalising easier

- Low vocal effort – high intensity output

Humans can hear a wide range of frequencies, from 16Hz to 16,000Hz. Sounds above this range are called ultrasonic (beyond hearing) and sounds below this range are called subsonic. Examples of ultrasonic sounds are the high pitched sounds of bats. Subsonic sounds tend to be felt as vibrations, like whale song.

Although we can hear this wide range, there is a band in the middle that we hear very well. This range is between 2,000 and 4,000Hz (2kHz - 4kHz). The reason we hear this range so well is that it's the frequency range in which a newborn baby cries. For obvious reasons, we're biologically programmed to have a response to that sound. As mentioned above, your response is dependent on context - if it's your own baby, crying at 4am, you'll want to tend to it; if it's someone else's baby, crying at 4am on a long-haul flight, you'll have a very different response! But no matter what your response is it's a sound you can't ignore.

a sound you can't ignore

When we engage twang, we emphasise this specific frequency range and prompt that response in our audience / listeners.

The image (above right) shows the effect of adding twang on the harmonics between 2kHz and 4kHz.

The image below shows the effect of adding twang on the harmonics between 2kHz and 4kHz.

The anatomy of twang

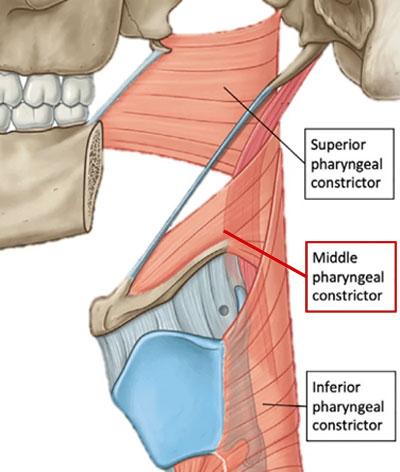

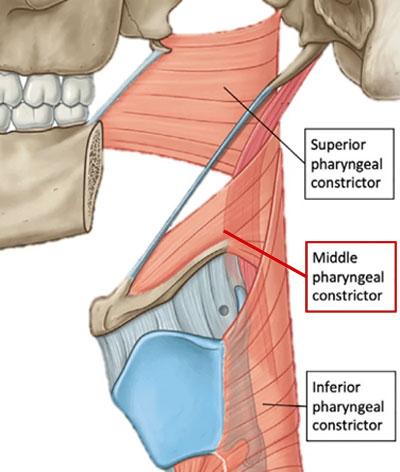

The intensification of twang comes from an intentional narrowing of the pharynx (throat). The pharynx has a number of 'pinch points' which can be usefully (and safely!) narrowed by the singer - this is how we form both language and Voice Qualities. These include obvious ones like the lips and tongue, but less obvious ones like the Pharyngeal Constrictors (swallowing muscles).

You can examine the role of these structures for yourself by simply whispering a sequence of vowel sounds (e.g. ee - ay - ah - oh - oo) or the lyrics to a song. You'll realise that it doesn't take much effort to shape the throat.

As far as adding twang is concerned, the two structures we're concerned with are the Middle Pharyngeal Constrictor and the Epilarynx - the area of the vocal tract immediately above the Epiglottis.

A lot of research into this topic has been undertaken in the last few years by Kerrie Obert and Chadley Ballantyne. I've summarised the most important takeaways in the following sections, but if you want to watch the entire video (a 'NATS Chat' from 2019) it's included here.

As mentioned above, twang can be added by narrowing the Middle Constrictor and/or the Epilarynx (individual singers can engage both). We'll examine each in turn.

Middle Pharyngeal Constrictor

The three pharyngeal constrictor muscles (Superior, Middle and Inferior) make up the majority of the pharyngeal wall (throat) and are used primarily for swallowing - food is literally squeezed down the oesophagus by contraction of each of these muscles in turn, from top to bottom.

The Middle Constrictor attaches to the hyoid bone, a small horseshoe shaped bone from which the larynx suspends. It lies just under the line of the jaw, in the centre of your throat. When you engage twang, you will feel narrowing around this area.

When the Middle Pharyngeal Constrictor narrows, it forms a separate resonating space which boosts the harmonics discussed earlier (between 2kHz and 4kHz).

If you've been told or taught that you shouldn't 'sing from the throat', this may seem like an odd sensation. But the narrowing of the MPC is perfectly safe and natural, so long as it's done without going into a full swallow manouevre which may also induce constriction in the False Vocal Folds, which is something we're looking to avoid. You can always identify False Fold constriction / pressed phonation as you'll feel a tickle or scratch sensation, or feel the need to cough. Tickle, Scratch, Cough are warning signs that you've gone too far.

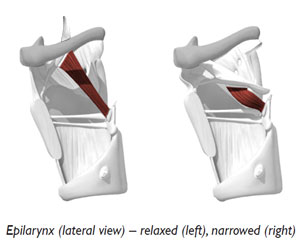

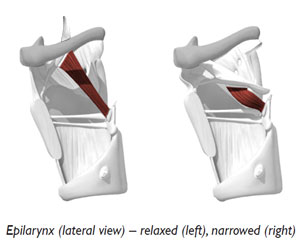

Epilarynx

The epiglottis is a small, leaf-shaped cartilage that protects your larynx. It acts like a lid on top of the larynx that opens to allow air to pass through when breathing and closes to prevent food and drink from entering the windpipe when swallowing. It's actually shaped like a chute, which helps food and drink to slide down more easily.

Normally, the epiglottis functions perfectly well but it can sometimes get a little out of sync and allow a small amount of food or drink to enter the airways, prompting a strong cough reflex. This is what is commonly known as 'something going down the wrong way'.

the concept of WIDE to NARROW is still vital to understand

Muscles attach to the epiglottis and also the arytenoid cartilages. When these muscles contract, they form a sphincter-like space referred to as the AryEpiglottic Sphincter (AES for short). When the AES narrows, it forms a separate resonating space, in much the same way as the Middle Pharyngeal Constrictor. It used to be thought that these muscles were solely responsible for lowering the epiglottis. However, recent research has shown that these muscles are not strong enough to work alone and that there needs to be an amount of tongue 'backing' to lower the epiglottis. This tongue backing also narrows the AES. It has also been proven that an open 'AH' vowel lowers the epiglottis, but does so without inducing any twang.

The newer understanding is that there IS a narrowing of the epilaryngeal space, but partially because of tongue root backing, not purely because of the aryepiglottic muscles. However, the concept of WIDE to NARROW is still vital to understand - however it's formed.

High and Low twang

This new understanding leads on to a more thorough understanding of twang, where we can form the same resonance boost in different ways, using the two structures above.

We now understand twang as two things - High twang and Low twang

Low Twang is formed by tongue backing and is used more in Classical singing (where it is also known as 'Squillo'). Low Twang can also produce a gathering of higher resonances known as the Singers' Formant Cluster.

High Twang is formed by narrowing the Middle Pharyngeal Constrictor and is used more in Commercial Contemporary music (CCM) (where it is also known as 'Edge')

How do I engage twang?

As mentioned earlier, adding twang to the sound simulates some very 'primal' sounds like a baby's cry. For that reason, when I'm working with a singer on twang for the first time, I use simple images to try and stimulate the singer's imagination. Once they've found a sound that works for them, they can 'reverse engineer' the anatomy, to explain the sensations they feel while making the twangy sound.

As these sounds are so intense, when first accessing them the singer's 'inner critic' may get involved, resulting in the singer backing away from the sensation. I remind the singer that these are the extreme versions of the sound, a little like tasting chilli pepper in isolation - on its own it's too pungent, but added into a recipe, it can give a meal a real boost.

I have a range of suggestions like "a bleating lamb", "an angry duck", "a hungry kitten", "a moped riding down the street" - over 20 in all, which I'll try with each singer until we find the one that works best for them. Once they have their preferred 'Twang Trigger', they can use it to sing through a melody, enjoying the volume boost they get without any increase in vocal effort. It's then a matter of moderating the degree of narrowing to match the dynamics of the song.

Once you've accessed your twang, your singing life becomes much simpler!

Learn to use twang

Andy is a full-time, professional vocal coach, not a school teacher, singer or pianist giving a few singing lessons in their spare time. Unlike a lot of voice teachers, Andy does not insist on long-term tuition, where students have to attend regular lessons, repeating the same exercises until their voice improves. You can attend as often as you like, but there's no compulsion to attend every week or every fortnight. In fact, many students only book sessions every 4 to 6 weeks.

Estill Voice Training™ is known for producing quick results. Quite often, Andy finds that long-standing problems can be fixed in the first few lessons. At your first session, Andy will give you an assessment of your abilities and draw up a plan that ensures you get to where you want to be, as quickly as possible.

If you're ready to take your voice to the next level, book a lesson with Andy today (see bottom of page).

Andy runs his studio from St Helens, so is ideally located for students in the Liverpool, Merseyside, Manchester, Lancashire and Cheshire areas. Please check out the separate pages for students from Liverpool, Merseyside, Warrington, Widnes / Runcorn, Wigan, Cheshire, Lancashire and North Wales.

For those unable to travel to the studio, or who are based overseas, Andy is also happy to teach online via Zoom. During the 2020 lockdown, Andy was able to continue teaching in this way to provide full service to his clientele. For more information on the equipment needed for an effective Zoom lesson, please check out the Online Lessons page.

Become the singer you've always wanted to be

Discover your true potential and take control of your future